Emissions to air

Emissions to air from the petroleum sector

Greenhouse gas emissions from the petroleum sector account for about one-quarter of Norway’s total emissions. Power from shore has been the most important measure for reducing these emissions. The increase in the number of power from shore projects that have been green-lighted since 2020 is a result of factors such as increased CO2 costs.

In this chapter:

The greenhouse gas emissions from the petroleum sector amounted to 10.9 million tonnes of CO2 equivalent (see fact box about different kinds of emissions) in 2024. This includes emissions from fixed and mobile facilities on the Norwegian continental shelf (NCS) and onshore process plants, meaning Kårstø, Kollsnes, Nyhamna, Melkøya, the Sture terminal and the oil terminal at Mongstad.

Of this, CO2 emissions amounted to 10.6 million tonnes. Methane emissions accounted for 10,871 tonnes or 0.3 million tonnes of CO2 equivalent. Emissions from the petroleum sector account for about one-quarter of Norway's overall greenhouse gas emissions. The sector is also a substantial source of NOX and NMVOC emissions.

Different kinds of emissions from the petroleum sector

Emissions to air from petroleum activities consist of more than the greenhouse gas CO2.

A brief overview of emission components other than CO2 follows below, as well as an explanation of the term CO2 equivalent:

Nitrogen oxides (NOx): A collective term for the nitrogen oxides NO and NO2, which are gases that have an acidifying impact on the environment.

Sulphur oxides (SOx): A collective term for sulphur dioxide (SO2), and sulphur trioxide (SO3).

Methane (CH4): In a 100-year perspective, methane (CH4) has a climate impact roughly 28 times as significant as the climate impact of CO2.

NMVOC (non-methane volatile organic compounds): A designation for volatile organic compounds with the exception of methane.

Black carbon: Black carbon refers to small particles that are formed in connection with incomplete combustion of fossil fuel and have a powerful warming effect.

CO2 equivalent: The overall warming effect from CO2 and methane is summarised as CO2 equivalent in the Norwegian Offshore Directorate's emission forecasts.

Methane and NMVOC also have an indirect impact in that they oxidise to CO2 over time and have an additional impact equivalent to pure CO2 emissions. This impact is included in the Norwegian Environment Agency's emission forecasts.

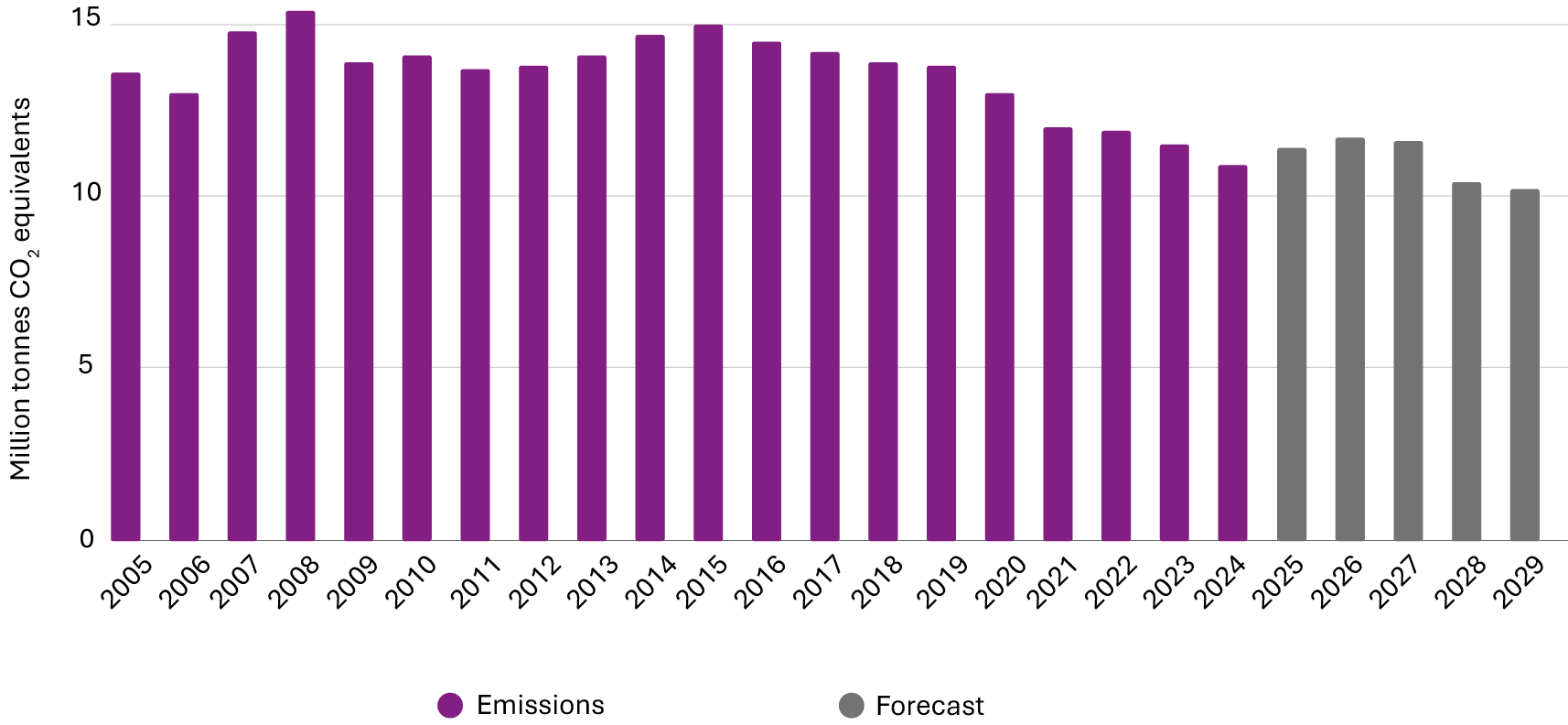

Figure 1 (below) shows annual emissions from 2005 to 2024, and a forecast up to 2029. The annual emissions of CO2 and CH4 have declined by 4.1 million tonnes of CO2 equivalent since 2015, despite production remaining relatively stable. This was primarily caused by multiple facilities being operated using power from shore in whole or in part. Emissions are expected to decline even further in the years ahead. This will take place despite a modest emissions increase over the short term.

Figure 1: Development in greenhouse gas emissions 2005-2024, and forecast up to 2029.

Emission sources

Energy generation on offshore facilities and onshore plants is the primary source of emissions to air in the petroleum sector.

A petroleum installation needs power for three primary use areas: generating electricity, operating equipment and generating heat. The power is generated by combusting gas in gas turbines.

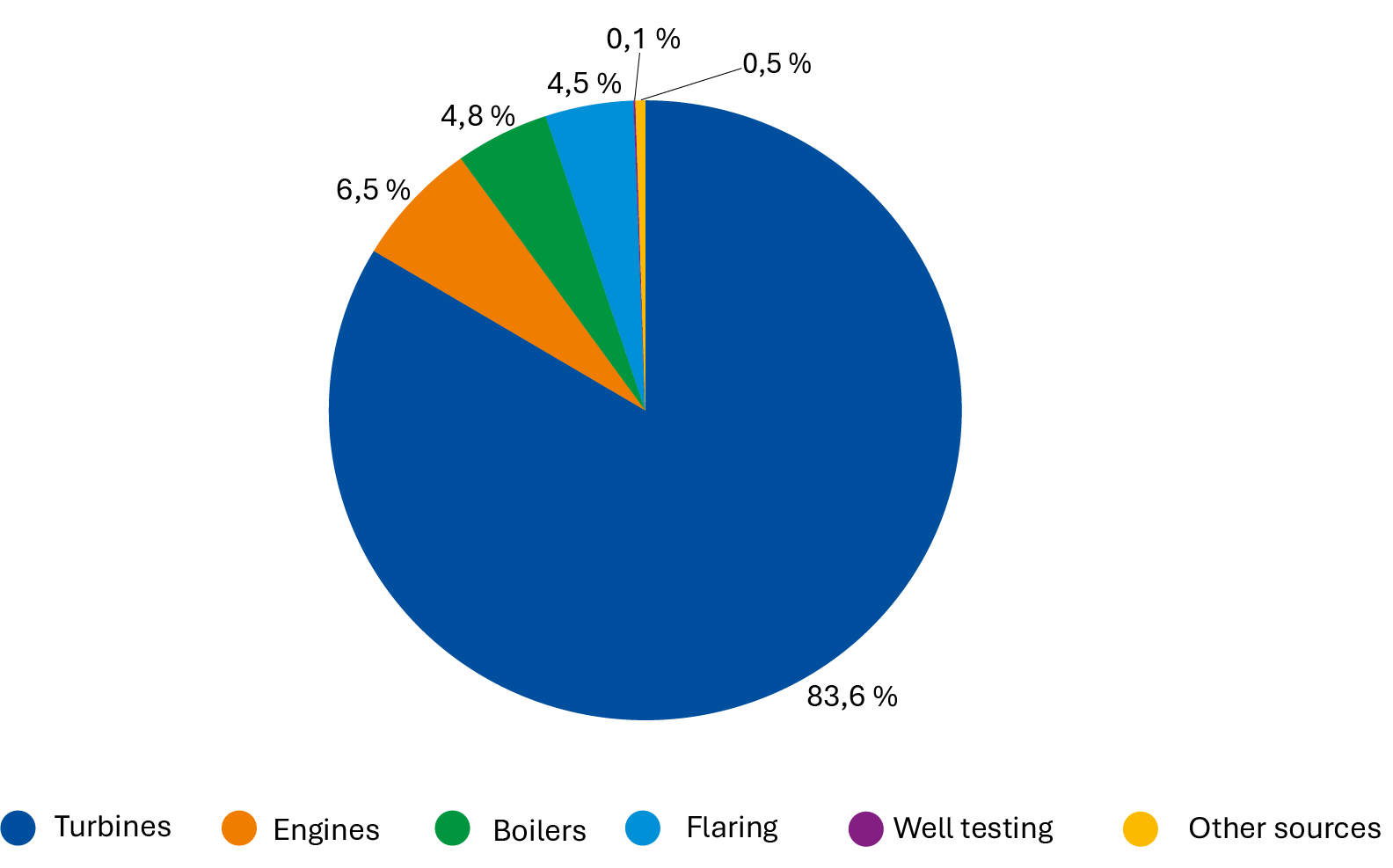

Gas turbines are the largest source of CO2 emissions from the NCS; see Figure 2. Diesel in motors is mainly used on mobile facilities, which means i.e. for drilling wells. In addition there are emissions from safety flaring of natural gas.

The largest sources of methane emissions is planned or unplanned direct emissions of natural gas to air, emissions associated with unburned natural gas in flares and turbines, and emissions in connection with storage and loading of crude oil.

Figure 2: Distribution of greenhouse gas emissions (CO2) by emission sources.

Measures to reduce emissions

Power from shore is the most important measure to reduce emissions from the petroleum sector. Replacing the power generated by gas turbines, in whole or in part, with power from shore, will reduce the emissions from the largest offshore emission source.

Work is also under way on other measures to reduce the emissions. Among these, the industry considers energy efficiency measures and reduced flaring to be the most important.

Energy efficiency measures

Energy efficiency measures include various measures that contribute to reduced energy needs and thereby reduced use of fuel gas in gas turbines. There are many options as regards energy efficiency measures, and these measures vary in scope, complexity, impact and costs. If energy consumption is reduced so that operations can be maintained with fewer gas turbines, this can result in relatively substantial energy savings.

Offshore wind

Other than power from shore, it is possible to reduce emissions using electricity from locally installed offshore wind turbines without a connection to the power grid. The emission reductions will not be quite as large as for power from shore, and the abatement cost will be higher. The facilities need a continuous supply of energy, so they will need to supplement with electricity from gas turbines when wind is not sufficient.

Gullfaks and Snorre are the only fields that receive electricity from offshore wind turbines, which comes from the Hywind Tampen wind farm. The development of Hywind Tampen took place with support from Enova and the NOx Fund. The wind farm is estimated to supply the fields with about 35 per cent of their annual need for electricity. Equivalent measures have been considered on Brage and Ekofisk, but they were rejected for financial reasons.

In time, installations can potentially be connected to offshore wind farms connected to the onshore power grid. Such wind farms can supply the facilities with electricity for large parts of the year, compared with electricity from local offshore wind with only a handful of turbines. Nevertheless, power from shore or continued use of gas turbines will be necessary periodically when there is insufficient wind power.

As of today, there are no such offshore wind farms operating on the shelf. The licensees on Ekofisk have considered connecting to the wind farm currently being planned in Sørlige Nordsjø II, but they chose to suspend the studies in 2025 due to excessive costs.

Carbon capture and storage

Equipment to capture and store CO2 from turbine exhaust (CCS) is challenging to install on existing facilities. Such equipment normally requires more space and weight capacity than what is available on the facilities. In other words, this technology is more relevant when developing new facilities. The licensees consider developing dedicated gas-fired power plants with CCS to supply existing facilities with electricity to be significantly more expensive than obtaining electricity from the onshore grid. This is why they have chosen not to proceed with this alternative.

Alternative fuels

Use of alternative fuels such as biofuels, hydrogen or ammonia, may be possible over the longer term. Access to and the price of fuel pose challenges. There is uncertainty associated with combustion in existing turbines and the modifications needed. Improvements in technological solutions and reduced costs will be necessary before such measures can potentially be adopted. Introducing alternative fuels could entail other types of risks, which will need to be handled.

Policy instruments to reduce emissions

The most important policy instruments to achieve reductions in greenhouse gas emissions from the petroleum sector are financial : taxes and participation in the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS).

The companies also need a permit pursuant to the Pollution Control Act and a flaring permit pursuant to the Petroleum Act.

Since they are subject to emission allowances in the EU's ETS system and taxes, the companies need to either reduce their emissions or pay for them. The emission costs have increased over time. In 2020, the level was about 860 2025-NOK/tonne, and today it is about 1860 NOK/tonne.

The Storting has adopted a gradual escalation of the CO2 tax, so the overall emission cost in 2030 shall amount to 2000 2020-NOK per tonne (equivalent to about 2400 2025-NOK). This also means a substantial increase in the CO2 cost moving forward, which the companies account for in their financial assumptions. The tax is adopted on an annual basis in connection with the Fiscal Budget.

See Report No. 1 to the Storting (2024-2025) and the bill and resolution Proposition 1 LS Supplement 1 (2021-2022) (Norwegian only).

Emission allowance requirement and CO2 tax

Emission allowance requirement

In 2024, 95 per cent of emissions in the petroleum sector were covered by the EU's Emissions Trading System. This entails an obligation to purchase allowances to emit CO2. The emission allowance price is determined in the emission allowance market. In 2024, the CO2 price in the EU's Emissions Trading System averaged EUR 66.60 or about NOK 775 per tonne of CO2. In early October 2025, it was about 78 EUR/tonne, or about 920 NOK/tonne (exchange rate of 11.8).

CO2 tax

In 2024, close to 86 per cent of emissions in the petroleum sector were subject to tax. The Act relating to tax on discharge of CO2 in the petroleum activities on the shelf stipulates that the companies must pay a CO2 tax for combusting gas, oil and diesel on the shelf, including the Melkøya onshore plant. There is also a tax for direct natural gas emissions, as well as for CO2 separated from petroleum and emitted to air. The CO2 tax for 2025 for combusting gas is 2.21 NOK/Sm3. Converted to NOK per tonne of emissions thus constitutes NOK 944.

Learn more about emission allowance requirement and CO2 tax.

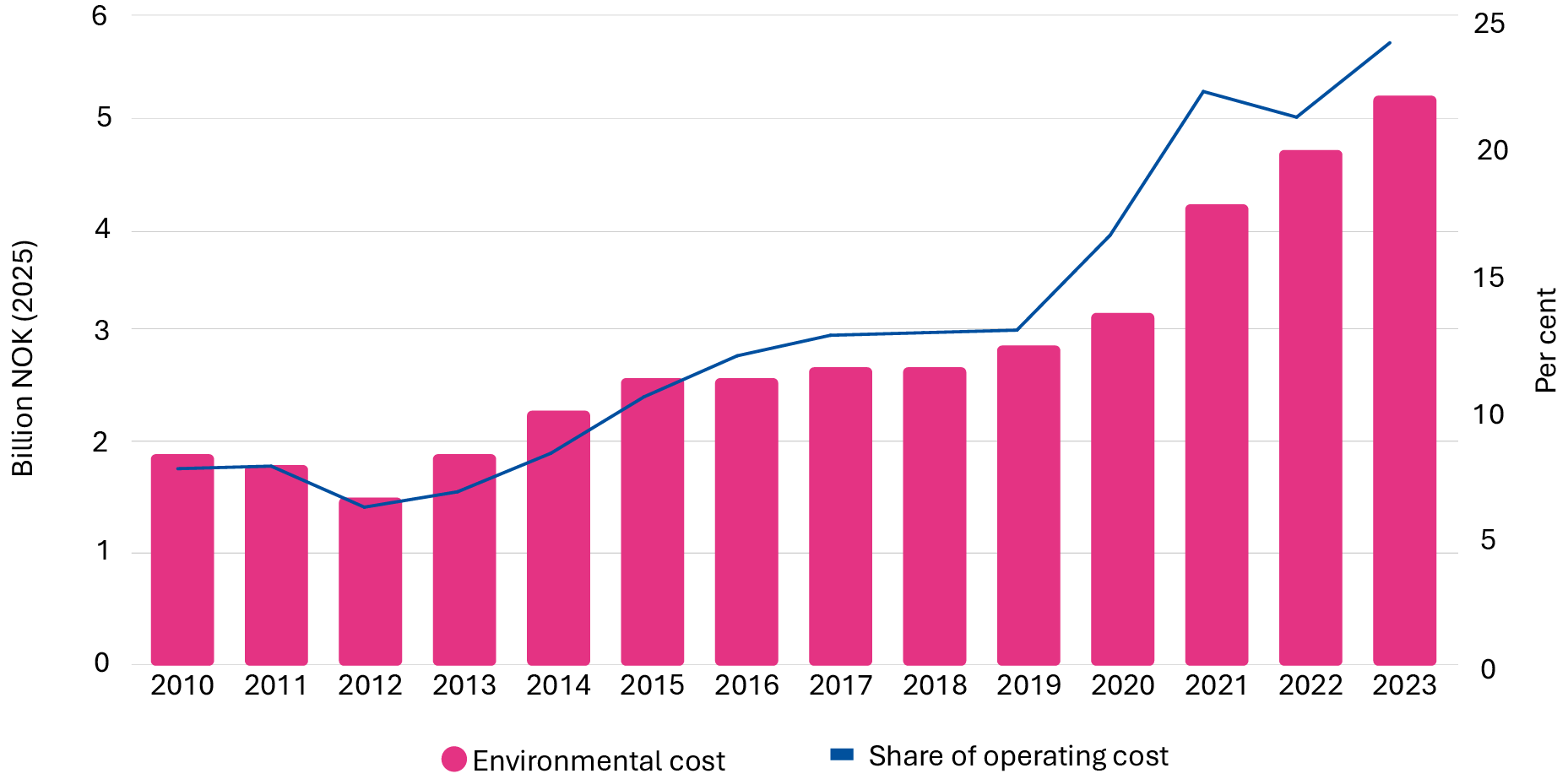

The increase in emission cost per tonne has led to a rising environmental cost on the fields over time. Higher environmental costs make up a substantial share of current costs for fields where energy generation takes place using gas turbines. Figure 3 (below) shows the development in environmental costs from 2010 to 2023 for fields where all energy consumption has been covered by gas turbines. For these fields, the environmental costs in 2023 accounted for nearly 24 per cent of operating expenses.

Figure 3: Development in environmental cost and share of environmental costs in per cent of operating costs for fields where all energy consumption is covered by gas turbines. The environmental cost here is the overall cost of CO2 emissions (tax and emission allowance requirement) and NOx tax. The latter constitutes about 3 per cent.

Major investments mean that a project to transition the energy supply to power from shore will require an extensive operating period in order to be profitable. According to current plans, the project now in the planning phase could be operational in 2032; see Chapter 5.

The companies' expected emission cost after 2030 is included in project profitability assessments. There is substantial uncertainty associated with developments in emission costs in the far future, and the companies will have different assessments regarding the size of this.

Profitability of power from shore projects

The profitability of a power from shore project is affected by a number of technical and economic factors. The most important economic elements will be discussed in the following.

Transitioning energy generation on a field from using gas turbines to power from shore may entail considerable investments. The investments can vary from facility to facility, depending on the cost of connecting to the onshore grid, the distance and the amount of electricity to be transmitted offshore and the extent of refitting and equipment to be installed on the facility. Read more in Chapter 3 of the 2020 Power from shore report.

Another significant cost is linked to purchasing electricity. This includes the grid tariff.

The gas, which is used as energy for the turbines, can be sold in the gas market given that there is available capacity to export the gas. This can generate substantial revenues.

Power from shore leads to reduced costs associated with greenhouse gas emissions: both the CO2 tax and costs linked to purchasing emission allowances. The size of future emission costs per tonne is a key assumption. In addition, there are costs saved in connection with gas turbine maintenance, minus costs associated with maintaining new power infrastructure.

If production on a facility needs to be shut down in connection with the refit, this leads to deferred revenue, which must be taken into consideration in the profitability calculations.

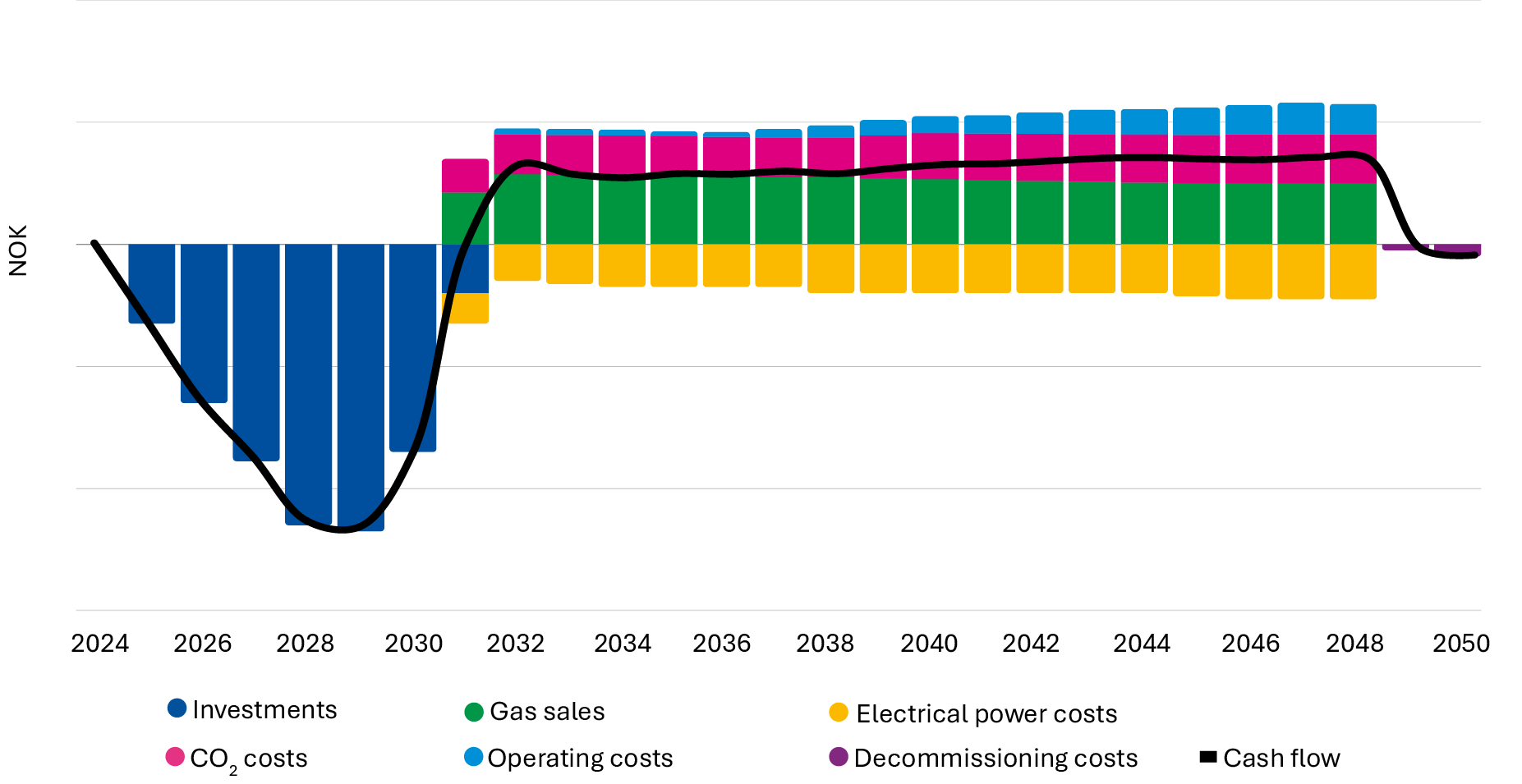

Figure 4: Outline – cash flow from a power from shore project.

The size of the overall cash flow for a power from shore project will also depend on the length of the operations phase with power from shore: The longer the operations phase, the higher the total cash flow.

In order to assess the profitability of such a project, the total net present value will be a key assessment criterion. This is in addition to the abatement cost; see separate fact box.

In addition to profitability estimates, the assessment of risk will be crucial in connection with a development decision. Changes in the size of the investments will typically have the greatest impact on the net present value. Experience has also shown that investments associated with refitting the facilities are the most difficult to estimate.

There are also other effects of power from shore that should be included in a comprehensive assessment. The 2020 report addresses a study by the Norwegian Ocean Industry Authority which shows that, overall, transitioning to operations with power from shore is positive for health, safety and the environment (HSE). There is also experience demonstrating that operational regularity is usually higher on fields with power from shore.

Power from shore projects will normally be extensive, and only profitable if there is a long expected lifetime. The companies' strategic assessments and assumptions regarding future changes to the framework conditions will also be important in connection with a development decision.

Measure cost

The Norwegian Offshore Directorate defines the abatement cost as the CO2 cost per tonne that yields a present value of zero with a 7 per cent discount rate. With this definition, the abatement cost indicates the minimum CO2 cost per tonne that is needed for the project to be profitable. If the expected future CO2 cost per tonne exceeds the abatement cost, a CO2 reduction project will be profitable. This calculation discounts both the cash flow and the reduction in CO2 emissions (which reflects revenue in the form of reduced CO2 costs).

There is also a different way to calculate the abatement cost. See Appendices C and D to the 2020 report for details about both methods.